Welcome to auteurism, a series of brief explainers on filmmakers worth knowing about // Today’s entry is on Ralph Bakshi, the director of Fritz the Cat, The Lord of the Rings, and Cool World // The end has lists of films to watch, articles to read, and media to consume to better understand Bakshi’s life and work.

The name may or may not ring a bell, but you know the work of Ralph Bakshi even if you don’t know you know it. You’ve likely come across a Fritz the Cat poster at your local comics or record store, caught snippets of the animated Lord of the Rings on Cartoon Network as a kid, or seen memes and stills of a young, pre-fame Brad Pitt with an animated buxom blonde Jessica Rabbit type in Cool World.

Bakshi is one of those “underground artists” whose influence is still felt everywhere in our culture. We passively absorb his oeuvre through the relics that the universe has kept in circulation. I know I’m not the only one out there whose love for Bakshi’s work runs deeper than that. Anyone with an illustration or animation background is likely to hold him in some sort of esteem. But his contribution to American art and pop culture in the 20th century and beyond deserves broader appreciation.

Born in 1938, Bakshi grew up in the poor, racially integrated neighborhood of Brownsville. “I lived in a very mixed neighborhood,” said Bakshi. “That allowed me to treat people as I treat them, but it also allowed me to look at people as they were.” He enjoyed the cultural melting pot of Brownsville's Black, Jewish, Irish, and Italian populous, and the freedom, in his words, of "nothing we had to live up to. We found that very important. In other words, nobody was chasing me to be a doctor or a lawyer or anything."

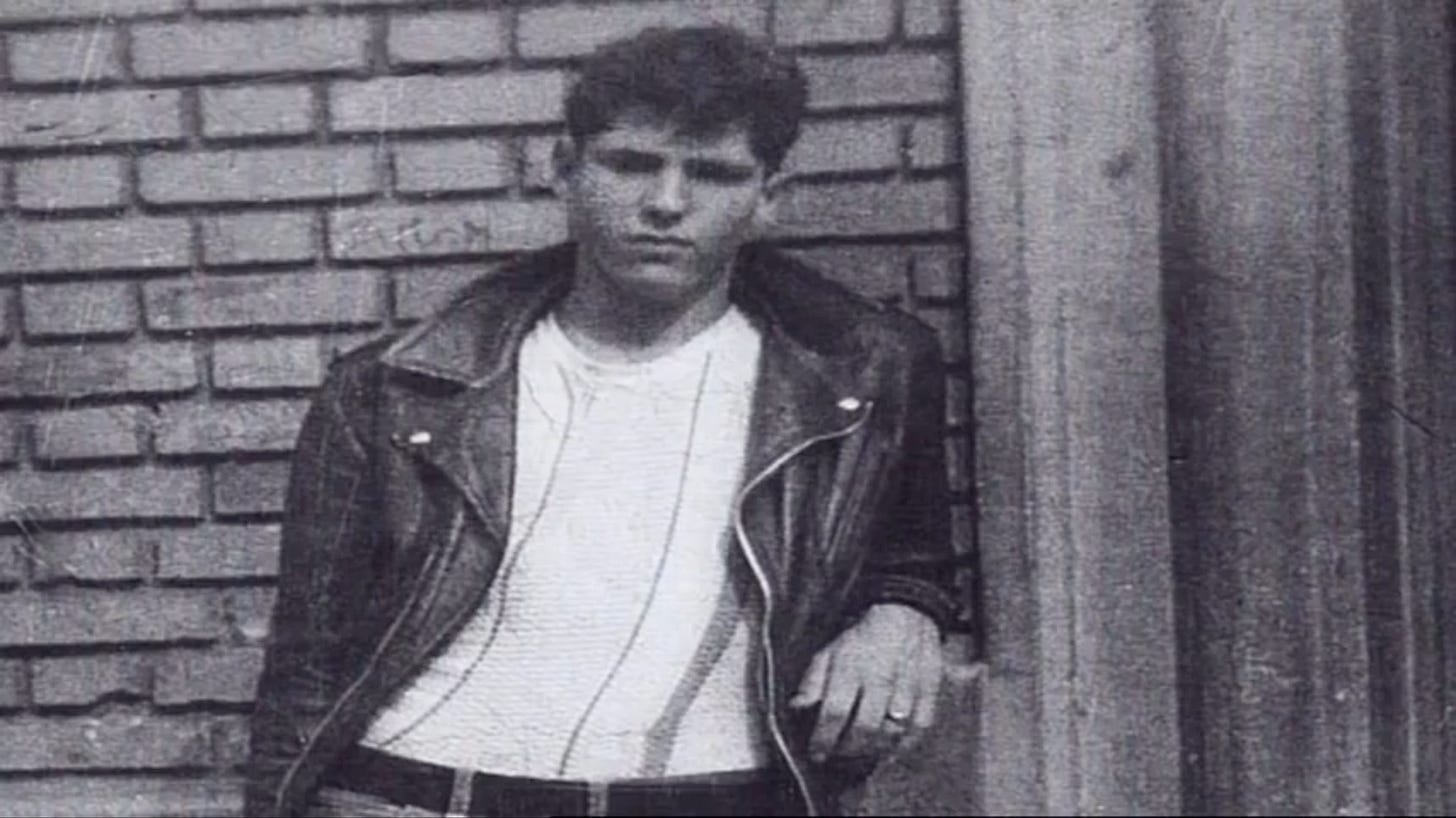

Bakshi would grow into his teens a natural mid-century rebel, showing little to no interest in academics, getting in trouble for starting food fights in the cafeteria and smoking in the boys room. At the same time, he was beginning to explore an interest in doodling and cartooning, documenting his life through drawings while also indulging in fantasy art — a pattern he’d follow throughout his career.

Bakshi drawings, age 16

Bakshi was eventually transferred to the Manhattan School of Industrial Art where he’d learn his first tricks of the cartooning trade, and eventually landed a job at Terrytoons animation studio. He started out as a cel polisher and painter, digging discarded drawings out of the animators' wastebaskets and taking them home to teach himself to animate on his own time. He was the only Jewish employee at Terrytoons and would get overlooked for promotions until he all but forced himself into the animation department.

After a year as an animation director at Terrytoons, Bakshi left and slid into a head-of-animation gig at Paramount Pictures. Unfortunately, the job would only last eight months as Paramount folded its animation department. With nowhere else to go, Bakshi founded his own animation studio and pitched a film to producer Steve Krantz called Heavy Traffic — a personal, experimental animated work for adults about modern inner-city life. Krantz said they’d need to pitch a pre-existing property to get any funding, so Bakshi suggested R. Crumb’s underground comic Fritz the Cat.

Though heavily marketed as “the first X-rated animated film,” Fritz the Cat is, as described by blogger evvyram, “a collage of episodes, scraps of insight, improvisation, rushed animation, Altman-esque overlapping dialogue, and chaotic editing all held together with a few common themes and sheer conviction.” R. Crumb’s hatred for the Fritz the Cat movie is ubiquitous to the property at this point, though I’ve never really understood why. If Bakshi’s Fritz the Cat is guilty of anything (besides introducing more of us to Crumb’s work), it’s adding a greater sense of self-awareness to Crumb’s grueling, despondent satire.

In both mediums, Fritz is an unlikeable, misogynistic college hipster whose "free spirit" antics mostly get the marginalized people around him in deeper shit. In a scene from the film that resonates today, Fritz incites a riot in Harlem and gets his friend Duke, a Black crow (the first and arguably most significant of the many racist Disney caricatures Bakshi would lampoon) shot in the process. As Duke's life fades, the sound of his slowing heartbeat is animated in a Dali-esque series of pool balls bouncing into red, pulsating holes. It's a vivid, early example of Bakshi's uncanny ability to be sad, humorous, playful, profound, provocative, disarming, and solemn all at once.

Fritz the Cat is a cult classic, a sardonic riff on the “happy times” and “heavy times” of the 1960s, and a surrealist document of a cultural movement's destructive limits. And it’s only a modest precursor to Heavy Traffic.

With the success of Fritz the Cat under his belt, Bakshi was finally able to make an original film focused on human characters. In a clearly autobiographical move, the protagonist of Heavy Traffic is an underground cartoonist who takes inspiration from the people on the streets of a dilapidated 1970s New York. The film is a blazing portrait of an America in tatters and the messy lives of the cartoon caricatures-turned-three-dimensional outcasts moving through its ruins. New York Times critic Vincent Canby ranked Heavy Traffic among the best films of 1973 alongside Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets and George Lucas's American Graffiti. To quote a tagline from the film's trailer, "it's animated, but it's not a cartoon. It's funny, but it's not a comedy. It's real, it's unreal, it's heavy," and it remains Bakshi's magnum opus.

Bakshi followed up Heavy Traffic with 1975's Coonskin, a film Quentin Tarantino described as an "urbanized retelling of the Uncle Remus' Brer Rabbit tales" and "hands down the most incendiary piece of work in the entire [blaxploitation] genre.”

"Bakshi, with zero timidity," wrote Tarantino, "challenged his audiences' sensibilities in ways that made all the other blaxploitation titles seem like the wish-fulfillment fantasies they were." It's hard to say whether the film succeeds in fully subverting the Western racial stereotypes it violently embodies. Still, there's enough there to suggest Bakshi’s intentions were pure and well worth the creative risks involved. "By using caricatures and stereotypes so outrageously," wrote Roger Ebert, "Bakshi forces us to SEE them, to deal with them, instead of letting them pile up in our unused but potentially mischievous subconscious baggage." For good or ill, Coonskin is both a vulgar product of its time and a defiantly forward-thinking experiment, and it shines a relentless light on the deep-rooted malignancies of America's enduring race problem.

After taking his animated Urban milieu about as far as it could go, Bakshi turned to the fantasy realm with Wizards, "a sword and sorcery tale of a new holocaust set ten million years in the future," as Tarantino puts it. Released the same year as Star Wars, Wizards is another modern sociological remix of the hero's journey, casting the magical, natural realm of elves, dwarves, and fairies on the light side and the mutated, post-nuclear remnants of humankind on the dark side. The film's villain is a dark wizard who uses old war technology and Nazi propaganda footage to incite his mutant army. Wizards is the clearest manifestation of Bakshi's anti-fascist, anti-war, anti-authoritarian sensibilities, and it builds a charming fantasy world that feels alive and vibrant — even in its bleakest, most apocalyptic moments.

With his next few projects, Bakshi would become a key figure in the development of rotoscope animation, a process defined by shooting live-action scenes and tracing over the individual frames (modern examples include Richard Linklater's Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly). For the first film of this era, an adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, rotoscope was a technique of necessity — a way for Bakshi to capture fluid, realistic movement and epic battle scenes on a modest budget to match the specificity of Tolkein's meticulously rendered Middle-earth. Unfortunately, the final film only amounts to half of Tolkein's trilogy, and a sequel was planned but fell through. But its imagery is so potent that Peter Jackson openly lifted some of it for his uber-successful live-action adaptation decades later.

Bakshi exploited rotoscope technology to great effect with American Pop (1981), a sweeping saga of 20th century American music, and Fire and Ice (1983), another dark sword-and-sorcery project and collaboration with artist Frank Frazetta. In many ways, American Pop is a more successful execution of rotoscope than the fantasy stuff, thanks in part to a propulsive music-video sensibility and urban-collage narrative.

Post-Fire and Ice, Bakshi took a nine-year break from features, turning to TV and reviving a popular Terrytoons character in Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures, a “Saturday morning cartoon show so hip you could show it on Saturday night.” He stacked his crew with young animators that would define the look and feel of cartoons in the ‘90s with projects like Ren and Stimpy, Animaniacs, and Batman: The Animated Series. In 1992, Bakshi returned to the big screen with Cool World, a live-action-meets-animation romp in the vein of Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Cool World is certainly no Roger Rabbit in production-value terms, and it’s a bit of a narrative mess thanks to studio-mandated rewrites that would alter its R-rated horror course to more marketable PG-13 territory. But its rough-around-the-edges look has only gotten better with age, and its animated sequences feel indescribably transgressive.

Bakshi slowly faded out of active work in the latter half of the ‘90s, making a few shorts for Cartoon Network and a short-lived HBO series. His most recent work to date, a kickstarter-funded swan-song short called Last Days of Coney Island, came out on Vimeo in 2015. By virtue of the medium to which he dedicated his life’s work, Ralph Bakshi is both a monumental figure of American independent cinema and a martyr to Disney’s outsized, sterilizing influence over the culture. I love Disney’s entire catalog of incredible hand-drawn animated films as much as the next guy, but there’s no question that the company’s early monopoly over the field sucked up a lot of energy and money away from artists like Bakshi who wanted to make it a more legit art form for experimental, grown-up storytelling.

As we head into an era of mass-decentralization in filmmaking, here’s hoping we unearth a legion of artists like Bakshi from all kinds of working class backgrounds — folks who can take the whole of American culture, warts and all, and filter it through an incendiary animated lens.

Bakshi Essentials:

Fritz the Cat

The Lord of the Rings

Fire and Ice

Cool World

Notable Shorts, Music Videos & TV:

To Read:

Ralph Bakshi Retrospective, Evvycology

Not for the Pixar Crowd: Ralph Bakshi on "Last Days of Coney Island", Simon Abrams

Review: Coonskin, Roger Ebert

To Watch/Listen:

Ralph Bakshi Interview, Cartoonist Kayfabe

If you liked the post, please hit the heart button below // It helps us reach more readers on Substack // Also, tell a film-loving friend to subscribe.

Follow me on Twitter // Read more of my writing: whoisandyandersen.com

Great article! When I was a kid I would watch Heavy Metal which felt like some forbidden relic to at that time because it was so unlike anything I knew haha. Heavy Metal and Fritz the Cat played a big part in helping to develop my personal tastes as a comic fan in particular. I still haven’t seen Wizards which I need to remedy. I do love his Lord of the Rings and especially Fire and Ice quite a bit!